The Rio Grande Basin is the sixth largest drainage basin in North America, encompassing an area of 570,000 square kilometers. However, the Rio Grande and its tributaries are dammed many times along their lengths, resulting in a high degree of modification to the hydrology and natural drainage patterns of this river system.

The Falcon Dam is the dam that sits the furthest downriver, just upstream of the Rio Grande Valley and the river’s mouth at the Gulf Coast. The dam was built in 1954 and impounds 3.3 million cubic meters of water. By way of this large impoundment, the dam provides water and electricity to the settled regions of the Rio Grande Valley and its surroundings.

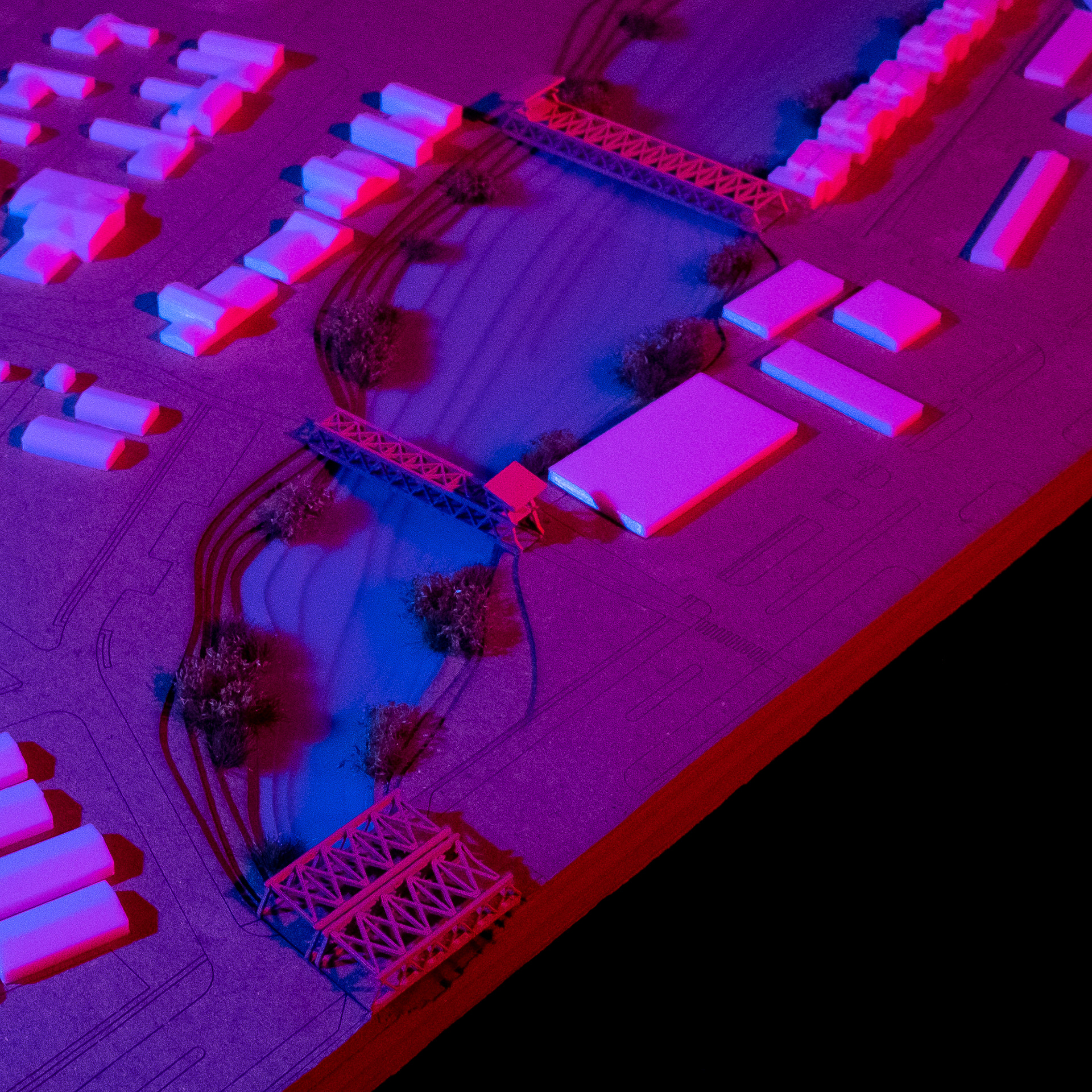

This map illustrates the natural and artificial hydrologies of the Rio Grande Valley

This map illustrates the urban extent and concentration of energy and water use in the Rio Grande Valley

This map illustrates the effect of the Falcon Reservoir on the surrounding climate

The proposed project takes form as an urban scheme in the city of Brownsville, re-negotiating the relationship between the largest city in the Rio Grande Valley and the damaged estuary it inhabits, the channels of which are known locally as resacas. This project to establish an Institute for Resaca Reclamation is guided by a charter that situates this institute bureaucratically within the administrative framework of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge.

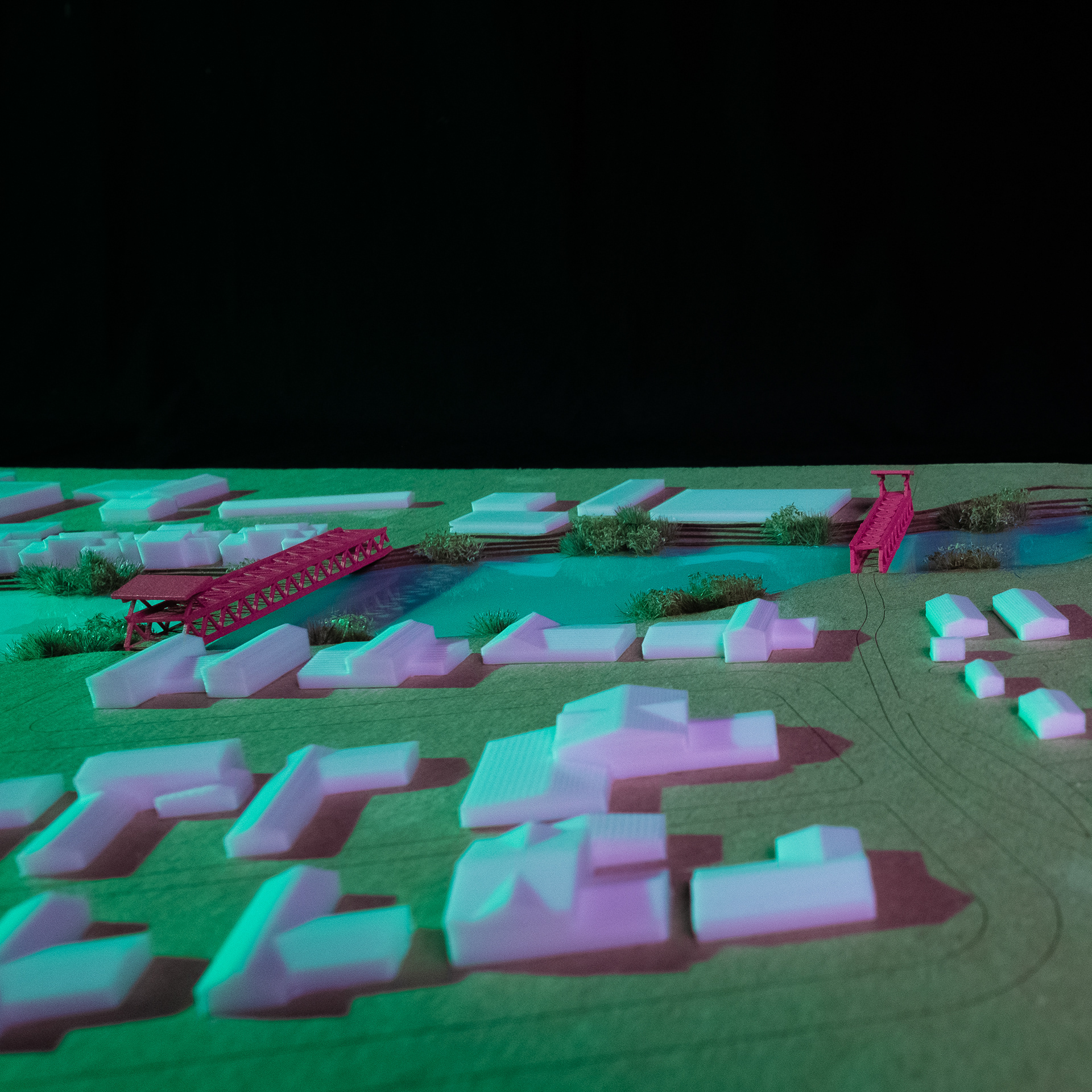

Before human interventions damaged the estuarine landscape, it would flood seasonally, converting the delta into a vast wetland and providing nutrients to support its biodiversity. However, due to human engineering of the estuary’s hydrology by damming infill, and channelization, the landscape is permanently damaged, no longer flooding in its natural cycles, and the resacas are left sequestered by the urban and suburban form. This urban scheme systematically intervenes, re-centering the delta landscape as not just the habitat for the city of Brownsville but as a vital post-natural ecosystem and reconnecting its components to each other and to the city.

The scheme is centered around a bike path corridor on a disused rail line that traverses the resacas across Brownsville, allowing for a human and infrastructural corridor that advances the intent of the project to remingle the urban and natural ecosystems into a post-natural condition.

The primary intervention in the resaca landscape is by the removal of the many embankments that have been installed to allow road and rail infrastructures to traverse the resacas. These embankments have only a small channel for drainage and interrupt the resaca edge. The scheme proposes the removal of these embankments and their replacement with truss bridges. The truss bridge subverts the pervasive embankment design by supporting the paved surface from above rather than below. The resaca edge becomes continuous beneath the new bridge, and the riparian habitat can be unified. The bridge design includes a field station perched atop one end that provides a locker for storing equipment and a location for monitoring the ecological intervention.

Eminent domain will be invoked to reclaim the resaca edge as federal land administered by the Refuge. Presently, many of these edges are privately owned, and they have been destroyed by the construction of artificial perimeters and retaining walls. The removal of these perimeters will be led by the Institute in order to create a fluid edge that supports riparian vegetation.

An active planting scheme is deployed following the embankment removal, wherein clusters of native flora are planted in 200-foot intervals along the reconnected resaca edge. Additionally, a water infrastructure is installed along the bike path corridor that supports the reintroduction of water movement and a modest inundation of the resacas twice a year, building on work by the Refuge to simulate floods in portions of the resaca landscape outside of the Brownsville city limits. The broken concrete left over from the removal of artificial perimeters is left piled in the landscape to be utilized by perching birds, which support a passive replanting scheme that builds upon the active scheme through their movement and propagation of seeds.

A building to house the Institute’s headquarters is proposed between a Brownsville city courthouse, the Cameron County courthouse, a series of law offices, and the parks and recreation department. Within this bureaucratic context, the building adopts a similarly hierarchical form where the upper administration of each of the Institute’s departments are located in second-floor trays. They are equal to each other but elevated above the subordinate work areas with clear supervisory sight lines, much like those provided by the field stations over the resacas.

The building’s interior embodies the urban and natural hybrid the project aims for at the territorial level by combining the greenhouse and office typologies at the architectural level. This is both a symbol of the relationships embedded in the urban scheme as well as a move to foster new relationships between the departments and within the office environment.